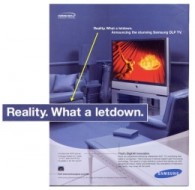

Reality. What a letdown…

What does technology want? It wants to give us choices, to give us lots of opportunities, proclaims Kevin Kelly, co-founder of Wired magazine. Once described as the “happy evangelist from Geekdom,” Kelly argues that technology enables us to “become, in principle, what we want to become.”

Google’s executive chairman Eric Schmidt would agree: “[G]lobal science has sort of no restrictions. If we get this right, I believe we can fix all the world’s problems.”

“Solutionism” is the term Evgeny Morozov uses to describe this mindset. In our technology-saturated culture, he sees solutionism as a “pervasive and dangerous ideology … an intellectual pathology that recognizes problems as problems based on just one criterion: whether they are ‘solvable’ with a nice and clean technological solution at our disposal.”

Or put another way, solutionism is “the idea that given the right code, algorithms and robots, technology can solve all of mankind’s problems, effectively making life ‘frictionless’ and trouble-free.”

For Morozov, ground zero for solutionism is Silicon Valley. Thus, “What does Silicon Valley want?” could be his reframing of Kevin Kelly’s question. And Samsung’s tag line for its new digital TVs could serve as the tag line for Silicon Valley’s cultural agenda: Reality. What a letdown.

In what ways has reality let us down? What are some of the “torments of existence” for which solutionism would propose a solution? Morozov offers several examples in a recent New York Times article, “The Perils of Perfectionism.”

· Seesaw is an app that allows you to ‘crowdsource absolutely every decision in your life.’ [T]he app lets you run instant polls of your friends and ask for advice on anything: what wedding dress to buy, what latte drink to order and soon, perhaps, what political candidate to support. … It used to be that we bought things to impress our friends. … Now this logic is inverted: if something impresses our friends, we buy it.

· Google Glass, the company’s overhyped “smart glasses,” which can automatically snap photos of everything we see and store them for posterity. To some, this can finally solve the problem of forgetting, a longtime ambition of many geeks, who have also been developing stamp-size cameras that can be worn on the lapel of a jacket and snap a picture — at set intervals of time — of things around us.

· “When your heart stops beating, you’ll keep tweeting” is the reassuring slogan greeting visitors at the Web site for LivesOn, a soon-to-launch service that promises to tweet on your behalf even after you die. By analyzing your earlier tweets, the service would learn “about your likes, tastes, syntax” and add a personal touch to all those automatically composed scribblings from the world beyond.

· This idea of obliterating forgetting was laid out by the visionary Microsoft computer scientist Gordon Bell in his highly provocative 2009 book, written with Jim Gemmell, “Total Recall: How the E-Memory Revolution Will Change Everything.” … Mr. Bell promised that new recording technologies would provide us with “enhanced self-insight, the ability to relive one’s own life story in Proustian detail, the freedom to memorize less and think creatively more.”

Twitter mortality, forgetting, and decision-making are just some of the everyday letdowns for which Silicon Valley offers a remedy. They “become ‘problems,’” Morozov argues, “simply because we have the tools to get rid of them — and not because we’ve weighed all the philosophical pros and cons.”

Solutionists err by assuming, rather than investigating, the problems they set out to tackle. Given Silicon Valley’s digital hammers, all problems start looking like nails, and all solutions like apps. …

It’s hard to defend America’s current political system, but it’s even harder to rally behind the solutionist project for one simple reason: the proposed Internet-powered ‘solution’ is not sold to us based on its inherent merits — of those we hear very little — but, rather, on the demerits of the existing system, be it partisanship or sleaze. Yes, the current system teems with imperfections, but imperfection might be the price to pay for a half-functioning democracy. There is, after all, little partisanship in North Korea.

At first glance, Evgeny Morozov may look like a polar opposite to the technology boosters of Silicon Valley. But he is no technology basher, certainly no Luddite. Morozov uses Google products, talks on a cell phone, and corresponds by e-mail. He flies around the world on modern airliners and uses PowerPoint when he gives TED talks.

Rather than boost or bash technology, Morozov is a realist—a concerned realist who would understand the impact of technology on our culture.

Learning to appreciate the many imperfections of our institutions and of our own selves, at a time when the means to fix them are so numerous and glitzy, is one of the toughest tasks facing us today. …

Whenever technology companies complain that our broken world must be fixed, our initial impulse should be to ask: how do we know our world is broken in exactly the same way that Silicon Valley claims it is? What if the engineers are wrong and frustration, inconsistency, forgetting, perhaps even partisanship, are the very features that allow us to morph into the complex social actors that we are?

“I wish it would dawn upon engineers that, in order to be an engineer, it is not enough to be an engineer,” wrote the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset in 1939. Given the cultural and political relevance of Silicon Valley — from education to publishing and from music to transportation — this advice is particularly worth heeding.

Evgeny Morozov is a Belarus-born student of the political and social implications of technology. He is the author of The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom and, most recently, To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism. He writes an internationally syndicated column for Slate and is a contributing editor at The New Republic. And he has been a visiting scholar at Stanford University and Georgetown University.

Morozov’s Times article, “The Perils of Perfectionism,” can be found here. “The Internet Won’t Save Us: Evgeny Morozov’s Stand against Technology Solutionism,” an interview by The Daily Beast, can be found here.

March 12, 2013

March 12, 2013

No comments yet... Be the first to leave a reply!