Learning about learning and human nature at the movies…

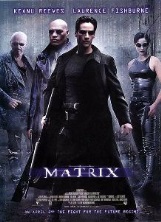

Lessons on teaching methods and educational philosophy are not what we typically expect at the movies. Most people expect lots of action and entertaining plots. The Matrix and The Karate Kid offer both—one a futuristic sci-fi thriller, the other an outsider’s battle with bullies.

But Dr. Micah Watson helps us see that these two films are also about teaching and learning. And more profoundly, they speak to our understanding of what it means to be human.

“Ten hours straight. He’s a machine.” So says a character in The Matrix about Neo, the newest protector against the evil forces trying to destroy humans. Though film viewers may be awed by Neo’s dizzying display of martial art skills and paramilitary expertise, what is even more remarkable is the method of his learning. Rather than devote long hours to practice and gradual improvement, Neo is literally hooked up to a machine through which everything he needs to know is uploaded to his brain. …

In The Matrix, the upload from a computer through a ‘brain-computer interface’ makes acquiring knowledge quick and effortless. But it can hardly be called learning—it’s a data dump.

The data dump of The Matrix is replaced in The Karate Kid by an attentive human instructor—a master teacher who has mastered karate himself.

The Karate Kid features Daniel Larusso, an Italian-American teenager who moves from New Jersey to a new high school in California. The cool kids at this school don’t play football or drive fast cars; they do karate. Unfortunately, Daniel manages to provoke the entire karate clique and soon has the bruises to show for it.

Enter Mr. Miyagi, the handy-man karate guru who takes Daniel under his wing and agrees to teach him. In a classic 1980s montage, Daniel arrives at Mr. Miyagi’s house only to find that his “training” is a series of menial and repetitive tasks: sanding floors, waxing cars, painting boards, and painting the house. Daniel eventually loses his temper, angrily accusing Mr. Miyagi of exploiting rather than teaching him. As the scene closes, Daniel reluctantly goes through the motions of each chore, but while he does so, Mr. Miyagi attacks him with various punches and kicks. Daniel is surprised to learn that each of the chores required him to internalize various movements that, when employed, blocked each successive attack. Daniel had unknowingly learned the basic tactics of defensive karate.

Dr. Watson continues by pointing out that these “competing visions of what it means to be human and to be a student” are both “well-entrenched in Western thought and practice.”

The first vision is best typified by Francis Bacon’s axiom that “knowledge is power.” In The New Atlantis, Bacon writes about a lost group of European sailors who stumble on a technologically and morally superior community in the South Pacific, where an elite cadre of scientists has utterly conquered nature. They manipulate nature so as to mimic, and improve on, all the goods that nature provides for the benefit of humanity. Nature, in this approach, is something to be molded and seems to set no limits on human action. The underlying view of human nature here is that there is no normative claim that arises from nature, human or otherwise, and thus that “nature” is just the stuff with which we can do as we like, even if it means transforming the very human nature that defines what “we” are. …

The second vision was first articulated by Aristotle. Here our habits make our character, and we acquire our habits by repetition. Suppose you’ve played a musical instrument for most of your life and have achieved some level of excellence. When you began, let’s say with the piano, much of what you did was composed of repetition. Scales. Endless scales. Your teacher chiding you to keep your back straight and wrists up. Nothing terribly beautiful resulted early on, but you kept at it and now you can play Chopin and Mozart. You’re an accomplished pianist. …

Moreover, and this is crucial, neither the apprentice musicians nor the novice ball players could appreciate what it really meant to be an excellent pianist or ball player while they were buried in all of the beginning drills. They had to trust others, most likely older and definitely wiser, who knew what they were doing. They had to take it on faith that someday their work would pay off. In other words, they had to trust someone whose expertise they could not, by definition, evaluate.

Education thus described is the passing on of practices, and therefore knowledge, by those who know to those who don’t, and it is done before the young can appreciate what they’re getting into. It is, as C.S. Lewis described, older birds teaching younger birds how to fly. By now it’s fairly obvious that this is the sort of education we see displayed in The Karate Kid.

What are the prospects for each of these visions in our current cultural climate?

Is it possible to adjudicate between these two approaches? One ought not be too sanguine about the prospects of persuading a committed proponent of robust cognitive enhancement that there is something more authentically human about the older way of learning. After all, the very notion of what should count as human is in question.

Still, one can consider these matters from the perspective of community over time. The Aristotelian/Karate Kid model elicits a generational dynamic in which we are taught, we learn, and then we teach. I submit that it is a more human and humane vision that takes into account individual weakness and limits while providing the means to pursue excellence by living closely with those who know more, and less, than we do at any particular stage in life. …

Sources & resources:

Micah Watson is the director of the Center for Politics & Religion and Assistant Professor of Political Science at Union University in Jackson, Tennessee. “Neo vs. the Karate Kid” was published in Public Discourse, an online publication of the Witherspoon Institute.

The development of the ‘brain-computer interface’ is more advanced than most people realize. For an update, go here and here.

January 30, 2014

January 30, 2014

So where does Aristotle/Karate Kid fit into the current B.F. Skinner behavior modification model currently in vogue?

In short, it doesn’t fit. The repetitive drills of the pianist and the basketball player and the coaching that encourage them are not necessarily examples of behaviorism. The Aristotle/Karate Kid model focuses on the nature of learners and the learning process. As Micah Watson points out, it “takes into account individual weakness and limits while providing the means to pursue excellence by living closely with those who know more, and less, than we do at any particular stage in life.” And that would naturally include positive as well as negative feedback. This feedback could come from the teacher or coach. It could and would come in the reality of the student’s performance—the wrong note, the missed jump shot as well as a beautiful performance of the Bach Chaconne or the three-pointer just before the buzzer.

What if we found a way to halve the amount of time required to play scales on a musical instrument before being able to play a piece really well? Would this be bad?

Would it be bad? Well, that would depend on how the halving of time was accomplished, right? Would you be willing to do it with a brain chip? I wouldn’t!