Why popular culture’s view of feminine beauty matters!

What is beauty? And who decides? In the pop culture arena, we all have a good idea. Ultimately, it’s the marketing executives in a broad range of intertwining industries— advertising, film, fashion, television, and magazine publishing.

But there is a growing resistance to what has been long considered the “idealized female image,” according to research summarized at Forbes.com. Using a “celebrity or model embracing a product or draping themselves across it” may do more harm than good when the potential customer is female.

The very presence of the model led to a loss of self-confidence as the consumer (female) looked at the advertisement. The difference between being turned away and making a purchase depended on how consciously aware they were of the model’s ideal features and beauty compared to their own self-image.

The consumer’s mental dialogue might run something like this, according to researcher Amitava Chattopadhyay.

Essentially when you see somebody who is very attractive, there is a natural comparison with yourself, that’s the human nature, it’s a default option when you say ‘how do I compare with this beautiful person?’ Given that this person has this idealized face and figure, most people don’t match up so you feel bad about yourself.

But this idealized image of feminine beauty needs to change and not for marketing reasons, according to Abby Schachter. She asks, “What happened to womanly beauty?” With the emphasis on “womanly.”

In a blog post at Acculturated – Pop Culture Matters, Schachter wonders, “why is girlie considered more beautiful than womanly?” The idealized feminine image is pre-pubescent.

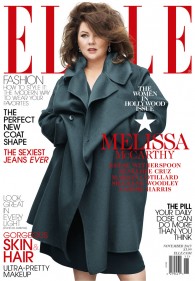

Behind Schachter’s post is a recent dustup in the world of glamor publishing. The November issue of Elle featured a cover photo of actress Melissa McCarthy wearing a wool coat. Elle was accused of trying to cover up the McCarthy’s plus-size figure.

Abby Schachter makes two significant observations.

By Hollywood standards, McCarthy is big. Of course, given how stick-skinny actresses strive to be, it is impossible to know what “plus-size” means in McCarthy’s case. Perhaps what counts as fat in the entertainment industry is actually quite normal-sized compared to the rest of America.

Be that as it may, Elle magazine is getting pummeled for supposedly “covering up” McCarthy on its “Women in Hollywood” cover. People are “disappointed” she isn’t showing more skin (she’s in a gorgeous wool coat and pounds of flawless make-up) and that “her body is being hidden.” McCarthy says she loves the cover and the fashion mag says it “stands behind” the photo.

The trouble with this brouhaha is that showing skin and wearing skimpy clothes has somehow become the go-to definition of being comfortable with your beauty. Is it not possible that beautiful can mean buttoned up and fully-dressed?

The other and possibly more significant point:

And here’s another reason this controversy is all wrong: One of the great things about McCarthy’s photo isn’t that she’s big or wearing a coat, so much as she looks like an adult woman as opposed to a girl-child. Take a look at two of the alternate Elle covers for the same issue: Reese Witherspoon and Shailene Woodley. Witherspoon is the mother of three and she looks dressed up like a tart in a cut-out Versace number and Woodley is in a bathing suit positioned like a lost little girl. Why isn’t Witherspoon dressing like the seriously mature actress that she is? And why is Woodley’s cover considered beautiful when she looks about 12-years-old with a body to match?

Why does popular culture’s view of feminine beauty matter?

It matters because popular culture is enormously powerful in shaping our affections and imagination and by extension our desires. In profound and often unconscious ways, our desires direct how we relate to the world and how we think about ourselves. In other words, popular culture is quite powerful in shaping our lived identity—the way we dress, the way we talk, the way we relate to each other, the way we spend our time and our money, the way we establish what’s important in life.

Understanding the social dynamics of popular culture is critical for those of us who would avoid being unwittingly shaped by it. Popular culture is not all bad, but it does distort, in many ways, what it means to be a healthy, thriving human being. In the spiritual realm, it is often a subtle and powerful force in what the New Testament writers call “worldliness”: “Do not be conformed to this world” (Romans 12: 2), “Do not love the world or the things in the world” (1 John 2:15).

Sources and resources:

“Does The Feminine Beauty Ideal Still Provide A Sales Bump?” is available at Forbes.com.

“What Happened to Womanly Beauty?” by Abby W. Schachter is available at Acculturated – Pop Culture Matters.

For more on the social dynamics of contemporary culture, see Desiring the Kingdom by James K. A. Smith, especially Chapter 3, “Lovers in a Dangerous Time.” In this book, Smith argues that there are “formative practices” that “shape and constitute our identities by forming our most fundamental desires and our most basic attunement to the world.” These formative practices, such as the popular culture conception of feminine beauty, make us certain kinds of people by shaping what we love.

The Introduction to Desiring the Kingdom is available online. It includes a brief overview of the formative practices that Smith calls “liturgies,” both secular and sacred, on pp. 24-26.

January 13, 2014

January 13, 2014

No comments yet... Be the first to leave a reply!