Why the Internet is not "just" another delivery system…

The research is starting to come in! And even the most ardent supporters of the Internet are having to rethink their enthusiasm for the world of “always connected.”

Since the arrival of the Internet, there have been questions about its cultural impact. Does it contribute to the rising incidence of ADHD and OC disorders? Is it addictive? Some observers claimed that these fears are similar to the anxiety produced by other new technologies—the printing press and the steam locomotive. One supporter of the Internet and mobile technology, a researcher writing in a prestigious psychiatric journal, snidely asked, “What’s next? Microwave abuse and Chapstick addiction?”

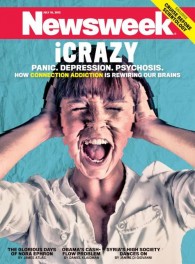

But now, even those most enchanted by the latest tablets and smart phones are having to mute some of their enthusiasm. Research on the impact of “always connected” was summarized in a July issue of Newsweek magazine. The cover read, “iCrazy: Panic. Depression. Psychosis. How Connection Addiction is Rewiring Our Brains.”

The first good, peer-reviewed research is emerging, and the picture is much gloomier than the trumpet blasts of Web utopians have allowed. The current incarnation of the Internet—portable, social, accelerated, and all-pervasive—may be making us not just dumber or lonelier but more depressed and anxious, prone to obsessive-compulsive and attention-deficit disorders, even outright psychotic. Our digitized minds can scan like those of drug addicts, and normal people are breaking down in sad and seemingly new ways.

The Newsweek article, written by Tony Dokoupil, is now available online under the title, “Is the Web Driving Us Mad?” As these technologies have become all-pervasive, Dokoupil argues, they’ve engendered a “life of continuous connection [that] has come to seem normal.”

In less than the span of a single childhood, Americans have merged with their machines, staring at a screen for at least eight hours a day, more time than we spend on any other activity including sleeping. Teens fit some seven hours of screen time into the average school day; 11, if you count time spent multitasking on several devices. When President Obama last ran for office, the iPhone had yet to be launched. Now smartphones outnumber the old models in America, and more than a third of users get online before getting out of bed.

Meanwhile, texting has become like blinking: the average person, regardless of age, sends or receives about 400 texts a month, four times the 2007 number. The average teen processes an astounding 3,700 texts a month, double the 2007 figure.

Even though the life of “continuous connection” may have come to seem normal, that doesn’t mean it’s healthy. Here’s an incomplete list of the problems that Dokoupil mentions, ranging from minor to rather severe.

· [M]ore than two thirds of … normal, everyday cyborgs … report feeling their phone vibrate when in fact nothing is happening. Researchers call it “phantom-vibration syndrome.”

· Peter Whybrow, the director of the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA, argues that “the computer is like electronic cocaine,” fueling cycles of mania followed by depressive stretches.

· It “fosters our obsessions, dependence, and stress reactions,” adds Larry Rosen, a California psychologist who has researched the Net’s effect for decades. It “encourages—and even promotes—insanity.”

· The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has never included a category of machine-human interactions. … When the new DSM is released next year, Internet Addiction Disorder will be included for the first time, albeit in an appendix tagged for “further study.”

· China, Taiwan, and Korea recently accepted the diagnosis, and began treating problematic Web use as a grave national health crisis. In those countries, where tens of millions of people (and as much as 30 percent of teens) are considered Internet-addicted, mostly to gaming, virtual reality, and social media, the story is sensational front-page news.

· “There’s just something about the medium that’s addictive,” says Elias Aboujaoude, a psychiatrist at Stanford University School of Medicine, where he directs the Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Clinic and Impulse Control Disorders Clinic. “I’ve seen plenty of patients who have no history of addictive behavior—or substance abuse of any kind—become addicted via the Internet and these other technologies.”

Even in this short list, we see a remarkable spectrum—from the mild “phantom vibration syndrome” to severely addictive behaviors. Dokoupil warns us not to kid ourselves about the role of the Internet in our own lives.

[T]he gap between an “Internet addict” and John Q. Public is thin to nonexistent. One of the early flags for addiction was spending more than 38 hours a week online. By that definition, we are all addicts now, many of us by Wednesday afternoon, Tuesday if it’s a busy week. Current tests for Internet addiction are qualitative, casting an uncomfortably wide net, including people who admit that yes, they are restless, secretive, or preoccupied with the Web and that they have repeatedly made unsuccessful efforts to cut back. But if this is unhealthy, it’s clear many Americans don’t want to be well.

Dokoupil’s overview of the impact of the Internet should cause all of us to stop for a “good long think”! How does time online affect me? My family? My neighbors? These are questions that everyone should be asking. The Church, though, will have additional issues to wrestle with. What are the values and the limits of the Internet for winning new Christians? What are the values and the limits of the Internet for discipling new converts? What impact does it have on our concept and practice of community?

There’s too much here to respond to in one short post—and too much that I’ve not grappled with myself. For these reasons, I’ll offer only three concluding remarks. But this is a very important topic that we’ll return to again and again over the next few weeks and months.

1. Tony Dokoupil’s closing comments requires serious attention. The “days of complacency should end”—we can no longer afford to accept digital culture without serious thought about what we want it to be. Reframing his remarks, I would ask, “Do we want it to be a useful, but limited tool, or do we want it to be a way of life?” Or, more precisely, a way of simulating life?

2. Ending complacency will require serious reading, thinking and discussing. It will also require finding a group of like-minded folks with whom to read, think, and discuss—in the flesh.

3. The Internet cannot be evaluated merely in terms of the content that it carries, as Dokoupil’s article amply demonstrates. These technologies shape us in powerful and often subtle ways. As we learned from Sherry Turkle in a previous post, “our little devices, those little devices in our pockets, are so psychologically powerful that they don’t only change what we do, they change who we are.”

Additional resources:

Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less From Each Other

Nicholas Carr, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains

Elias Aboujaoude, Virtually You: The Dangerous Powers of the E-Personality

August 17, 2012

August 17, 2012

Comments are closed.