The Last Christian on Earth (2): The Sandman Effect**

It’s quite likely that more people have been shamed out of their faith than have been argued out of it. But when most Christians think of defending the faith, they think of making arguments. The everyday challenges from the culture rarely register as areas for concern. Ideas do have consequences, but so does the culture.

In Memorandum 2, “The Sandman Effect,” the master spy explains this strategy for subverting the Church by exploiting its cultural drowsiness.

Not surprisingly, Christians see themselves as “believers,” and for most of them that is about all that matters. They may be vague about what they believe, and vaguer still about why they believe, but they believe, and that is all they worry about. Fortunately for us, very few of them bother to look into the deeper dimensions of believing. After all, how can they be expected to understand the subtleties of belief in a world in which believing itself is hard enough? Down the centuries a dedicated minority always explored the intellectual dimensions of belief, and this has been dangerous to us at times. But even they mostly tended to overlook the social dimensions. This oversight was our opportunity.

The spy master continues with an explanation of how social situations either undergird or undermine the faith.

[T]he degree to which a belief (or disbelief) seems convincing is directly related to its “plausibility structure”—that is, the group or community that provides the social and psychological support for the belief. If the support structure is strong, it is easy to believe; if the support structure is weak, it is difficult to believe. …

The Church is the Christian faith’s working model; its pilot plant; its future in embryo; its colonial outpost. So, if we can work on the Church as a social body until it is weak, shallow, distorted, hypocritical, or whatever, then it’s all up with the truth of the faith. Christian apologists can muster all the best arguments in the world, but they will not seem true. More accurately, they may be credible intellectually. But they won’t be plausible, and credibility without plausibility is tinny and unconvincing.

You can understand, then, our need to undermine the Christian faith through the Church, not so much at the level of truth as at the level of plausibility. Uproot Christians physically from a well-functioning community or alienate them inwardly from a poorly functioning one, and the rest of our job will take care of itself. There is a French saying that the Breton peasant checks his faith at the left-luggage office in the Gare Montparnasse on arriving in Paris. But the same is true of the student from a Christian home checking his faith at his first university seminar, or of anyone changing worlds. On entering the new world, the old becomes implausible, and soon its faith becomes incredible too.

Irony apart, the Church’s occupation with credibility and neglect of plausibility is typical of her cultural weakness. Without a feel for the social dimension of believing, the Church is like a person paralyzed from the neck down—quite insensible to the further damage being inflicted on her.

“The Sandman Effect” is the pivotal strategy for undermining the Church since it focuses on a vital but unguarded arena. To counter this strategy, as well as other subversive challenges, the Church must develop what is best described as cultural apologetics. This approach does not ignore the importance of ideas. Rather, it brings additional defensive tools to bear, beginning with the interpretation of the “impact of everyday experience” on all that we know and believe. It also assesses how everyday life unconsciously shapes our actions and ethical decisions. In sum, cultural apologetics seeks to provide an accurate understanding of contemporary culture as well as the requirements for engaging this culture on the basis of historic Christian convictions.

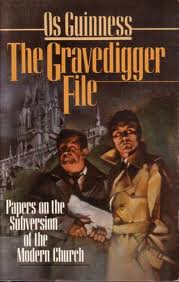

**A note on this series of posts: The literary device of The Last Christian on Earth is similar to C. S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters. Here though, a master spy, the Deputy Director, writes a series of memos to an operative outlining strategies and giving instructions on how to subvert the modern Church. Os Guinness, an Oxford-trained sociologist, uses this device to help translate concepts from the social sciences into ideas that relate to faith and discipleship. This book was originally published in 1983 under another title, The Gravedigger File: Papers on the Subversion of the Modern Church

October 29, 2012

October 29, 2012

Comments are closed.