Following Jesus in a world without windows…

“The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be.” Thus runs one of the most concise statements of the materialism that is at the heart of modernity. With this proposition, Carl Sagan began a book-length exploration and explanation of the universe entitled Cosmos (1980). In a universe filled with immense beauty and great mystery, Sagan assumed that natural physical reality is all there is. There is no God, no soul, no heaven, no supernatural, no sacred—there is nothing that transcends the material world.

Decades before physicist Sagan wrote Cosmos, theologian Rudolph Bultmann set about accommodating Christianity to this modern scientific worldview. He talked of “demythologizing” the New Testament—stripping the gospel proclamation of its supernatural elements.

The cosmology of the New Testament is essentially mythical in character. …

Can Christian preaching expect modern man to accept the mythical view of the world as true? To do so would be both senseless and impossible. It would be senseless, because there is nothing specifically Christian in the mythical view of the world as such. It is simply the cosmology of a pre-scientific age.

Man’s knowledge and mastery of the world have advanced to such an extent through science and technology that it is no longer possible for anyone seriously to hold the New Testament view of the world—in fact, there is no one who does. …

Now that the forces and the laws of nature have been discovered, we can no longer believe in spirits, whether good or evil.

It is impossible to use electric light and the wireless and to avail ourselves of modern medical and surgical discoveries, and at the same time to believe in the New Testament world of spirits and miracles. …

Rudolph Bultmann is only one of a long list of Christians—Protestants as well as Roman Catholics—who have taken their cues from elite secular culture. Their project is to redefine religious reality in secular terms, both at the level of thought and action. This loss of the transcendent is called secularization.

“A world without windows” is how sociologist Peter Berger describes this secularized view of the world. He also calls it the “prison of modernity.” Bultmann the theologian, as much as Sagan the scientist, is an inmate of this prison. Both agree that a modern scientific view of the cosmos requires reality to be interpreted as a closed system of natural cause and effect—a system without signs of transcendence.

For all of us, living in an increasingly secular age presents a constant temptation to live as if there is no transcendence, as if there is no God. This temptation arises not just from the ideas of thought leaders such as Sagan, Bultmann, or the New Atheists. Ideas do have consequences, as Richard Weaver has taught us. But so does everyday experience. In an essay entitled “For a World with Windows,” Peter Berger offers insights into just how this happens.

[The] social formations of modernity bring about habits and mind-sets which are unfavorable to the religious attitude. They encourage activism, problem-solving, this-worldliness, and by the same token they discourage contemplation, surrender, and a concern for what may lie beyond this world. Put simply, modernity produces an awful lot of noise, which makes it difficult to listen to the gods.

To this should be added the causal factor of pluralization. Through most of history people have lived in cohesive communities, which provided a stable social-psychological base (“plausibility structure”) for meta-empirical certitudes. Modernization shatters or fragments such communities, forcing people to exist in a cacophony of divergent world views and ipso facto making moral and religious certainty hard to come by. This means that urbanization and “urbanity” (as carried today by mass education, mass mobility, and the media of mass communication) are also agents of secularization. What is more, looking back to the beginnings of the process some three hundred years ago, secularization has become much more diffused and greatly accelerated as one get closer to the present time, simply because its various institutional ad sociocultural “carriers” have come to be more widely and firmly established.

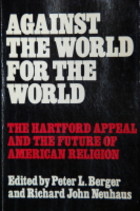

Peter Berger’s essay was included in Against the World for the World (1975). This collection of essays was written by several authors in response to the Hartford Appeal, a document produced by a group of men and women concerned about “the future of religion in America.”

The renewal of Christian witness and mission requires constant examination of the assumptions shaping the Church’s life. Today an apparent loss of a sense of the transcendent is undermining the Church’s ability to address with clarity and courage the urgent tasks to which God calls it in the world. This loss is manifest in a number of pervasive themes. Many are superficially attractive, but upon closer examination we find these themes false and debilitating to the Church’s life and work.

Many of these themes are included in the list that forms the body of the Hartford Appeal.

1. Modern thought is superior to all past forms of understanding reality, and is therefore normative for Christian faith and life.

2. Religious statements are totally independent of reasonable discourse.

3. Religious language refers to human experience and nothing else, God being humanity’s noblest creation.

4. Jesus can only be understood in terms of contemporary models of humanity.

5. All religions are equally valid; the choice among them is not a matter of conviction about truth but only of personal preference or lifestyle.

6. To realize one’s potential and to be true to oneself is the whole meaning of salvation.

7. Since what is human is good, evil can adequately be understood as failure to realize human potential.

8. The sole purpose of worship is to promote individual self-realization and human community.

9. Institutions and historical traditions are oppressive and inimical to our being truly human; liberation from them is required for authentic existence and authentic religion.

10. The world must set the agenda for the Church. Social, political, and economic programs to improve the quality of life are ultimately normative for the Church’s mission in the world.

11. An emphasis upon God’s transcendence is at least a hindrance to, and perhaps incompatible with, Christian social concern and action.

12. The struggle for a better humanity will bring about the Kingdom of God.

13. The question of hope beyond death is irrelevant or at best marginal to the Christian understanding of human fulfillment.

Unfortunately, these themes are still prominent in American culture as well as in the mindset of many contemporary Christians. And our task now, just as then, is to continually examine the assumptions that are shaping today’s church. The Hartford Appeal can be found online along with a very helpful paragraph of commentary for each point. Even though most of the signers do not subscribe to an evangelical theology, this does not detract from the cogency of the cultural analysis summarized under each of the thirteen themes.

May 14, 2013

May 14, 2013

Comments are closed.