Why it’s important to let children fail…

The family is in bad shape. Divorce, single parenting, hard economic times, and parents who are overly busy and distracted are a few of the contributing factors.

The problems of poor parenting gets everyone’s attention—from organizations such as Focus on the Family and the Institute for Family Studies (at the University of Virginia) to a host of family observers such as Brad Wilcox and Maggie Gallagher. In the counseling setting, helping children who grew up in difficult circumstances requires therapists to “re-parent” their patients by offering corrective insights and experiences.

But what about too much parenting—where the child is over-supervised and overprotected? There’s also a need to “re-parent” the over-parented.

Marriage and family therapist Lori Gottlieb has found that overprotected young people are a growing segment of her clientele. She’s come to believe that an obsession with our children’s well-being may in fact doom them to unhappiness as adults.

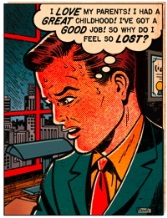

I met a patient I’ll call Lizzie. Imagine a bright, attractive 20-something woman with strong friendships, a close family, and a deep sense of emptiness. She had come in, she told me, because she was “just not happy.” And what was so upsetting, she continued, was that she felt she had nothing to be unhappy about. She reported that she had “awesome” parents, two fabulous siblings, supportive friends, an excellent education, a cool job, good health, and a nice apartment. She had no family history of depression or anxiety. So why did she have trouble sleeping at night? Why was she so indecisive, afraid of making a mistake, unable to trust her instincts and stick to her choices? Why did she feel “less amazing” than her parents had always told her she was? Why did she feel “like there’s this hole inside” her? Why did she describe herself as feeling “adrift”?

I was stumped. Where was the distracted father? The critical mother? Where were the abandoning, devaluing, or chaotic caregivers in her life?

As I tried to make sense of this, something surprising began happening: I started getting more patients like her. Sitting on my couch were other adults in their 20s or early 30s who reported that they, too, suffered from depression and anxiety, had difficulty choosing or committing to a satisfying career path, struggled with relationships, and just generally felt a sense of emptiness or lack of purpose—yet they had little to quibble with about Mom or Dad.

Instead, these patients talked about how much they “adored” their parents. Many called their parents their “best friends in the whole world,” and they’d say things like “My parents are always there for me.” Sometimes these same parents would even be funding their psychotherapy (not to mention their rent and car insurance), which left my patients feeling both guilty and utterly confused. After all, their biggest complaint was that they had nothing to complain about!

At first, I’ll admit, I was skeptical of their reports. Childhoods generally aren’t perfect—and if theirs had been, why would these people feel so lost and unsure of themselves? It went against everything I’d learned in my training.

But after working with these patients over time, I came to believe that no florid denial or distortion was going on. They truly did seem to have caring and loving parents, parents who gave them the freedom to “find themselves” and the encouragement to do anything they wanted in life. Parents who had driven carpools, and helped with homework each night, and intervened when there was a bully at school or a birthday invitation not received, and had gotten them tutors when they struggled in math, and music lessons when they expressed an interest in guitar (but let them quit when they lost that interest), and talked through their feelings when they broke the rules, instead of punishing them (“logical consequences” always stood in for punishment). In short, these were parents who had always been “attuned,” as we therapists like to say, and had made sure to guide my patients through any and all trials and tribulations of childhood. As an overwhelmed parent myself, I’d sit in session and secretly wonder how these fabulous parents had done it all.

Until, one day, another question occurred to me: Was it possible these parents had done too much?

The answer is “yes,” these parents have done too much! Gottlieb goes on to cite a varied group of experts who agree with her own conclusions. For example, Dan Kindlon, a psychologist and Harvard lecturer, has written a book entitled Too Much of a Good Thing: Raising Children of Character in an Indulgent Age.

If kids can’t experience painful feelings, Kindlon told me when I called him not long ago, they won’t develop “psychological immunity.”

“It’s like the way our body’s immune system develops,” he explained. “You have to be exposed to pathogens, or your body won’t know how to respond to an attack. Kids also need exposure to discomfort, failure, and struggle. I know parents who call up the school to complain if their kid doesn’t get to be in the school play or make the cut for the baseball team. I know of one kid who said that he didn’t like another kid in the carpool, so instead of having their child learn to tolerate the other kid, they offered to drive him to school themselves. By the time they’re teenagers, they have no experience with hardship. Civilization is about adapting to less-than-perfect situations, yet parents often have this instantaneous reaction to unpleasantness, which is ‘I can fix this.’”

In an article entitled “Why Parents Need to Let Their Children Fail,” Jessica Lahey recounts her experiences as a teacher and reports on a study of over-parenting at Queensland University of Technology.

Over-parenting is characterized in the study as parents’ “misguided attempt to improve their child’s current and future personal and academic success.” In an attempt to understand such behaviors, the authors surveyed psychologists, guidance counselors, and teachers. The authors asked these professionals if they had witnessed examples of over-parenting, and left space for descriptions of said examples. While the relatively small sample size and questionable method of subjective self-reporting cast a shadow on the study’s statistical significance, the examples cited in the report provide enough ammunition for a year of dinner parties.

Some of the examples are the usual fare: a child isn’t allowed to go to camp or learn to drive, a parent cuts up a 10 year-old’s food or brings separate plates to parties for a 16 year-old because he’s a picky eater. Yawn. These barely rank a “Tsk, tsk” among my colleagues. And while I pity those kids, I’m not that worried. They will go out on their own someday and recover from their overprotective childhoods.

What worry me most are the examples of over-parenting that have the potential to ruin a child’s confidence and undermine an education in independence. According to the authors, parents guilty of this kind of over-parenting “take their child’s perception as truth, regardless of the facts,” and are “quick to believe their child over the adult and deny the possibility that their child was at fault or would even do something of that nature.”

This is what we teachers see most often: what the authors term “high responsiveness and low demandingness” parents. These parents are highly responsive to the perceived needs and issues of their children, and don’t give their children the chance to solve their own problems. These parents “rush to school at the whim of a phone call from their child to deliver items such as forgotten lunches, forgotten assignments, forgotten uniforms” and “demand better grades on the final semester reports or threaten withdrawal from school.” One study participant described the problem this way:

I have worked with quite a number of parents who are so overprotective of their children that the children do not learn to take responsibility (and the natural consequences) of their actions. The children may develop a sense of entitlement and the parents then find it difficult to work with the school in a trusting, cooperative and solution focused manner, which would benefit both child and school.

These are the parents who worry me the most–parents who won’t let their child learn. You see, teachers don’t just teach reading, writing, and arithmetic. We teach responsibility, organization, manners, restraint, and foresight. These skills may not get assessed on standardized testing, but as children plot their journey into adulthood, they are, by far, the most important life skills I teach.

I’m not suggesting that parents place blind trust in their children’s teachers; I would never do such a thing myself. But children make mistakes, and when they do, it’s vital that parents remember that the educational benefits of consequences are a gift, not a dereliction of duty. Year after year, my “best” students–the ones who are happiest and successful in their lives–are the students who were allowed to fail, held responsible for missteps, and challenged to be the best people they could be in the face of their mistakes.

Links for sources and resources:

“How to land your kids in therapy” by Lori Gottlieb.

“Why Parents Need to Let Their Children Fail” by Jessica Lahey.

“The Overprotected Kid” by Hanna Rosin.

“The Play Deficit” by Peter Gray.

May 19, 2014

May 19, 2014

Comments are closed.