Teaching Freud and Lewis at Harvard (for 30 years)…

Sigmund Freud was the sole subject of the seminar that Dr. Armand Nicholi began teaching at Harvard in 1967. Student reaction was mixed. Half of the students agreed with Freud, but the other half disagreed strongly. The second group was disturbed by Freud’s militantly materialistic worldview.

The students found Freud’s works very interesting, but unbalanced. … They wanted to know who would be a good counterpoint, someone who would be able to defend and define the spiritual worldview that Freud attacked.

Dr. Nicholi’s responded by adding the writings of C. S. Lewis to the seminar: “When I added Lewis as a counterpoint, the discussion in class ignited.”

As a committed Christian, Lewis provided an excellent counterpoint to Freud’s worldview. But until age 32, he shared Freud’s brand of militant atheism and even used Freud’s reasoning to defend his beliefs. Lewis’s conversion came while teaching at Oxford and engaging in discussions with a group of Christian intellectuals that included people like Hugo Dyson and J. R. R. Tolkien.

Dr. Nicholi is fascinated by the process that led to Lewis’s conversion—a process that he discusses at some length in The Question of God. He has studied the conversion experiences of students and offers several parallels between their conversions and that of C. S. Lewis.

1. First, all the experiences occurred within the context of a modern, liberal university where the climate tended to be hostile to such experiences.

2. Second, both Lewis and the students observed in the lives of people they admired some quality they found missing in their own lives. Lewis observed this in the lives of the great writers as well as certain members of the Oxford faculty; the Harvard students, in the lives of other students. They were clearly influenced by their peers.

3. Third, both Lewis and each of the students made a conscious exertion of their wills to open their minds and examine the evidence. Lewis began to read the New Testament in Greek; the students tended to join Bible study groups on campus. They became convinced of the historical reliability of these documents and came to understand the Central Figure not as one who died two thousand years ago, but as “a living reality” who made unique claims about Himself and with whom they had a personal relationship

4. Forth, both Lewis and each of the students, after their conversion, found their new faith enhanced their functioning. They reported positive changes in their relationships, their image of themselves, their temperament, and their productivity. People who knew Lewis and those who knew the students before and after their transition confirmed these changes.

In searching for answers to “the question of God,” Dr. Nicholi suggests that we all may have a bit of both Freud and Lewis in us.

One part raises its voice in defiance of authority, and says with Freud, “I will not surrender;” another part, like Lewis, recognizes within our selves a deep-seated yearning for a relationship with the Creator. …

So we owe it to ourselves to look at the evidence, perhaps beginning with the Old and New Testaments. Lewis also reminds us, however, that the evidence lies all around us: “We may ignore, but we can nowhere evade, the presence of god. The world is crowded with Him. He walks everywhere incognito. And the incognito is not always easy to penetrate. The real labor is to remember to attend. In fact, to come awake. Still more to remain awake.”

Dr. Armand Nicholi’s experience of teaching the seminar on Freud and Lewis is nicely summarized in an article, “The Question of God,” in the September 19, 2002 edition of the Harvard University Gazette.

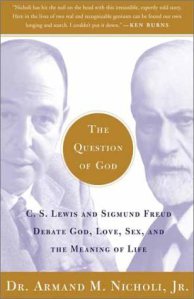

The Question of God: C.S. Lewis and Sigmund Freud Debate God, Love, Sex, and the Meaning of Life is a remarkable read and highly recommended.

June 9, 2014

June 9, 2014

This is how my father taught me the Bible growing up: by contrasting the World’s way to God’s way. I think he got some things wrong and especially caricatured the World’s way, but no matter: the spirit of what he taught me was what mattered; I could easily self-correct the caricatures and factual errors. It is not easy to understand the importance of doing the compare & contrast in the first place. After all, religion is just old mythology, right? We know how to do things, now, better than ever!

Luke, I assume you’re being ironical in the last part of your comment. But just in case that’s not your intent, here are three comments, without starting a long discussion of the second and third.

1. Take a look at the Question of God. It’s an excellent example of the contrast/compare method of teaching.

2. “Religion is just old mythology.” — Perhaps this is true of most religion, but I’d argue that Christianity is different. It can’t be put better or more succinctly than it was by C. S. Lewis: “Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth … Christianity is God expressing Himself through what we call ‘real things’.” Christianity has to power to change and shape individual lives and wider cultures. It also happens to be historically true.

See Lewis’s “Myth Became Fact” in God in the Dock.

3. Some things we know how to do better—but most we don’t. It’s the better things that are now in decline. Remember, along with others, Alasdair MacIntyre taught us that we live in a time “after virtue.”

I was being ironical. 🙂 I have read the book; it’s excellent! On my list is to do an in-depth study of the progress narrative; do you have suggestions for this research project?