The virtue of listening—because there are no little people…

Hearing is one of our natural senses, but listening is more. Listening requires focus and attention. In fact, good listening is just another way of talking. It speaks clearly—it says, you’re important. What you have to say—both your thoughts and feelings—are worthy of my consideration. Good listening dignifies the speaker.

Good listening—focused and attentive—travels in the company of several other virtues: patience, empathy, unselfishness, courtesy, kindness, compassion, respect, and gratitude. And probably many others besides.

But without the company of other virtues, listening is easily corrupted. Stephen Covey, the late management guru, pointed out that “Most people do not listen with the intent to understand; they listen with the intent to reply.”

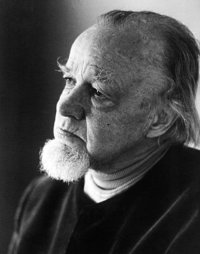

“Intent to understand” was the hallmark of missionary and apologist Francis Schaeffer, well known for his ability to listen—whether in the living room of his home in Switzerland or in a Q&A session in a large auditorium. In L’Abri, the story of their lives in Switzerland, his wife Edith described Schaeffer’s work as a ministry of conversation.

Rather than studying volumes in an ivory tower separated from life and developing a theory separated from the thinking and struggling of men, Fran has been talking for thirteen years now to men and women in the very midst of their struggles. He has talked to existentialists, logical positivists, Hindus, Buddhists, liberal Protestants, liberal Roman Catholics, Reformed Jews and atheist Jews, Muslims, members of occult cults… brilliant professors, brilliant students and brilliant drop-outs! He has talked to beatniks, hippies, drug addicts, homosexuals and psychologically disturbed people…. The answers have been given, not out of academic research (although he does volumes of reading constantly to keep up), but out of this arena of live conversation. He answers real questions with carefully thought out answers which are real answers….

Jerram Barrs, former Schaeffer associate, writes that Schaeffer “was terribly distressed when people would come to his home at the point of giving up their faith because no one in their church would take their questions seriously.” No one would listen!

Dr. Barrs continues,

I remember one young woman who came to L’Abri filled with pain because of the response of her parents when she raised questions about the Christian message. Her father was a pastor, but as a young teenager she began to have doubts and she wrote down some of her doubts and questions in her personal journal. One day her mother started reading through this journal (though it was private) and was horrified to read there the struggles her daughter was having. She shared the journal with her husband and they threw her out of her home, declaring that she must be “reprobate” because of the doubts she had expressed. She was then just 16 years old!

This is an extreme example, but all of us who worked in L’Abri with Francis Schaeffer could share many horror stories like this. This kind of situation broke his heart, and he would devote himself to listening for hours to the struggles and questions of those who came to his home. He would say, “If I have only an hour with someone, I will spend the first 55 minutes asking questions and finding out what is troubling their heart and mind, and then in the last 5 minutes I will share something of the truth.”

Some who came to the Schaeffers’ home were believers struggling with doubts and deep hurts like the girl I just mentioned. Some were people lost and wandering in the wasteland of twentieth-century Western intellectual thought. Some had experimented with psychedelic drugs or with religious ideas and practices that were damaging their lives. Some were so wounded and bitter because of their treatment by churches, or because of the sorrows of their lives, that their questions were hostile, and they would come seeking to attack and to discredit Christianity.

But, no matter who they were or how they spoke, Schaeffer would be filled with compassion for them. He would treat them with respect, he would take their questions seriously (even if he had heard the same question a thousand times before), and he would answer them gently. Always he would pray for them and seek to challenge them with the truth. …

In addition to his deep compassion for people in their struggles and in their lost state, Schaeffer also had a strong sense of the dignity of all people. The conviction that all human persons are the image of God was not simply a theoretical theological affirmation for him; nor was it just a wonderful truth to be used in apologetic discussion. It was a passionate shout of his heart, a song of delighted praise on his lips, just as for David in Psalm 8:

What is man that you are mindful of him,

the son of man that you care for him?

You made him a little lower than the heavenly beings

and crowned him with glory and honor.

The truth that we are the image of God, a truth that is at the heart of all Schaeffer’s apologetic work, is, for him, a reason to worship God. This conviction of the innate dignity of all human persons had many consequences for Schaeffer. He believed and practiced the belief that there are no little people. He invited people into his home who were damaged in body and mind and he treated them with the same dignity and compassion as the most brilliant or accomplished visitors. …

In L’Abri, Edith Schaeffer tells the story of their remarkable ministry which the Schaeffers founded in their home in 1955.

Dr. Art Lindsley’s “Profiles in Faith: Francis Schaeffer (1912–84)” is a very helpful overview of the Schaeffer’s lives and ministry.

The quotes from Jerram Barrs, currently Professor of Christian Studies and Contemporary Culture and Resident Scholar of the Francis A. Schaeffer Institute Covenant Theological Seminary, can be found in “Francis Schaeffer: The Man and His Message.”

February 3, 2015

February 3, 2015

Comments are closed.