Why the transgendering of Bruce Jenner is as American as apple pie…

Yes, what Bruce Jenner has done is as profoundly American. It advances a strain of American culture clearly articulated in the late 1800s by Walt Whitman’s epic poem, Song of Myself: “I Celebrate myself, and sing myself, And what I assume you shall assume.”

Having grown up in Quaker circles, Whitman replaced their theology of an “inner light” with his own radical, and heretical, vision of religious freedom. God is dethroned by the Self: “And nothing, not God, is greater to one than one’s self is.”

“I hear and behold God in every object, yet understand God not in the least,

Nor do I understand who there can be more wonderful than myself”

Whitman’s private religion of the individual Self was very much in sync with the thinking of an increasing number of his contemporaries, such as Henry David Thoreau and Emily Dickenson. According to Roger Lundin, Whitman was an early forerunner of what was described in the 20th century as the therapeutic self and the emotive self by Philip Rieff and Alasdair MacIntyre, respectively.

In The Triumph of the Therapeutic, Rieff writes that “Religious man was born to be saved, psychological man is born to be pleased.”

The wisdom of the next social order … would not reside in right doctrine … but rather in doctrines amounting to permission for each man to live an experimental life.

MacIntyre’s emotivist self, as described by Lundin, is another way of describing the increasingly dominant cultural character that elevates “veneration of the individual Self” above the authority of traditional beliefs, Christian and otherwise.

The emotivist self must consider itself free of claims of truth and the demands of the ideal, as it embraces the “temporary contract” and foregoes the security of “permanent institutions.” It accepts the fact that in contemporary culture, “truth has been displaced as a value and replaced by psychological effectiveness.”

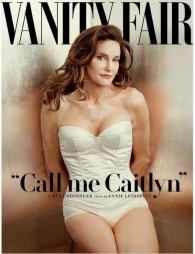

These three illustrations—Whitman’s Song of Myself, Rieff’s therapeutic self, MacIntyre’s emotivist self—are just three examples of a powerful cultural trend that has reshaped American culture over the past two centuries. In fact, without this deep cultural transformation, the Bruce to Caitlyn transition could not have occurred.

Will Wilkerson, writing for The Economist, thinks that the regnant self is here to stay.

The social forces that brought us to the Caitlyn Jenner moment are irreversibly ascendant. The gulf between the anguished vehemence of religious conservatives and the timidity of their brightest political lights is a sign of the times.

This is not to say that conservatives are being bullied by cultural liberals or are ashamed of their deepest beliefs, as [David] French, [writing for National Review], seems to think. Rather, the silence may reflect a dawning realisation that “our deepest beliefs” are not quite what we thought they were.

Wilkerson provides a sketch of what this weightlessness of “our deepest beliefs” looks like.

One of the enduring puzzles of America is why it has remained so robustly religious while its European cousins have secularised with startling rapidity. One stock answer is that America, colonised by religious dissenters and lacking an officially sanctioned creed, has always been a cauldron of religious competition and, therefore, innovation. The path to success in a competitive religious marketplace is the same as the path to success in business: give the people what they want.

Americans tend to want a version of Americanism, and they get it. Americanism is a frontier creed of freedom, of the inviolability of individual conscience and salvation as self-realisation. The American religion does Protestantism one better. Not only are we, each of us, qualified to interpret scripture, but also we each have a direct line to God. You can just feel Jesus. In my own American faith tradition, a minority version of Mormonism, the Holy Spirit—one of the guises of God—is a ubiquitous, pervasive presence. Like radio waves, you’ve just got to tune it in.

In a magisterial study, “The American Religion”, Harold Bloom maintains that the core of the inchoate American faith is the idea of a “Real Me” that is neither soul nor body, but an aspect of the divinity itself, a “spark of God”. To find God, then, is to burrow inward and excavate the true self from beneath the layers of convention and indoctrination. Crucially, this personal essence cannot fall under the jurisdiction of the “natural law” of God’s creation. Just as God stands outside His creation, so does the authentic self, which just is a piece of God. “[T]he American self is not the Adam of Genesis,” Mr Bloom writes, “but is a more primordial Adam, a Man before there were men or women.” Roman Catholic teachings about the obligatory roles of man and woman in the created natural order live on in the American religion as a faint and fading ancestral memory, but they are flatly at odds with the central American dogma of the “Real Me” as a bit of original divinity that stands apart. Indeed, from the perspective of the American religion, as Mr Bloom explains it, a moral code based on something as debased as “nature” offensively denies our inherent divinity. “No American concedes that she is part of nature,” Mr Bloom says. Ms Jenner certainly has not conceded it.

In this light, Mr French’s contention that Ms Jenner is “surgically damaged” smacks of a crudely materialistic philosophy that roots moral identity in the dispensation of genitalia. Far from “damaged”, Ms Jenner’s medical transfiguration is a glorious example of the American faith in action. She has refashioned mere nature to better reflect the hard-won truth of the divinity within.

Ms Jenner, it bears mentioning, is also a committed Christian. In the Washington Post Josh Cobia relates what Ms Jenner, then known as Bruce, taught him about Jesus, and life, at a non-denominational evangelical church they both attended. “Jesus wasn’t one to turn away from those the world had labelled broken,” Mr Cobia concluded. “He was the one who would walk toward them with open arms.”

The tolerant Jesus of Mr Cobia and Ms Jenner may not be the Jesus of Thomas Aquinas or Martin Luther or John Knox or John Wesley. He is a Jesus perhaps more thoroughly invested in the “autonomous eroticised individualism” of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman than any first-century reinterpretation of the Judaic law. But that is the American and still-Americanising Jesus of many millions of believers who, like Caitlyn Jenner, attend non-denominational evangelical churches, and who, like Caitlyn Jenner, vote Republican.

“The game isn’t over, but the outcome is not in doubt,” according to Will Wilkerson.

Jenner of Malibu is a leading indicator not of the secularisation of America, but of the ongoing Americanisation of Christianity. There’s no point dying in the last ditch to defend Old World dogma against the transformative advance of America’s native faith. Especially not if it will leave you out of step with the growing number … who find divinity by spelunking the self.

Wilkerson’s conclusion is difficult to refute. In fact, his case can be made more substantial when we look beyond the popular culture arena that he examines. The therapeutic/emotivist self has been enshrined in the highest law in the land—not merely in the hearts of many Americans. The Supreme Court of the United States, in Planned Parenthood vs. Casey (1992), put it this way:

At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.

Sources and resources:

“Conservative politics and the American religion: The Caitlyn Jenner moment” by Will Wilkerson was published on June 9, 2015 by The Economist.

June 18, 2015

June 18, 2015

Comments are closed.