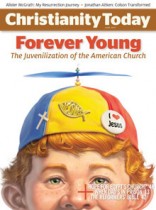

The Juvenilization of American Christianity…

American Christianity refuses to grow up. “We’re all adolescents now!”

Beginning in the 1930s and ‘40s, a quiet revolution began in American churches. It occurred in all segments of Christianity, but it has been most notably “successful” in the evangelical and conservative wing of the Church. This quiet revolution has resulted in the “juvenilization of American Christianity,” according to historian Thomas Bergler.

Juvenilization is the process by which the religious beliefs, practices, and developmental characteristics of adolescents become accepted as appropriate for adults.

Writing in Christianity Today, Bergler provides a brief history of this quiet revolution. It began with the admirable goal of bringing the Gospel to young people in a rapidly changing culture. But it has had unintended consequences.

Juvenilization happened when no one was looking. In the first stage, Christian youth leaders created youth-friendly versions of the faith in a desperate attempt to save the world. Some hoped to reform their churches by influencing the next generation. Others expected any questionable innovations to stay comfortably quarantined in youth rallies and church basements. Both groups were less concerned about long-term consequences than about immediate appeals to youth.

In the second stage, a new American adulthood emerged that looked a lot like the old adolescence. Fewer and fewer people outgrew the adolescent Christian spiritualities they had learned in youth groups; instead, churches began to cater to them.

As adolescent spiritualities set the agenda for churches, churches began to change. Increasingly, the main reason people gave for going to church became “enjoyment.”

Youth ministries and juvenilization contributed to this surprising outcome by making the Christian life more emotionally satisfying. Passion was in, duty was out. This kind of individualized, emotional connection to God sustained religious interest in a changing society in which custom, tradition, and social pressure would no longer motivate people to care about faith or attend church.

Not surprisingly, in the process of adapting to the new immature adulthood, churches started looking a lot like youth groups. Contemporary churches appeal to thousands of Americans by providing an informal, entertaining, fast-paced worship experience set to upbeat music. Everything done in these churches to reach “unchurched” people was already being done in the YFC rallies of the 1950s. And this parallel is not coincidental.

How many evangelical pastors have started their careers as youth pastors over the past 40 years? To take one highly influential example, Bill Hybels first experimented with his seeker-friendly model and church market research while serving as a youth pastor in the 1970s. The white evangelical churches that are growing the fastest in America are the ones that look most like the successful youth ministries of the 1950s and ’60s.

A prominent manifestation of “juvenilized Christianity” is what Christian Smith has labeled moralistic therapeutic deism—a new faith described in two previous posts, Soul Searching, five years on and A return of pagan Christianity? Citing Smith’s research, Thomas Bergler reminds us that

[E]ven those [young people] who are highly involved in church activities are inarticulate about religious matters. They seldom used words like faith, salvation, sin, or even Jesus to describe their beliefs. Instead, they return again and again to the language of personal fulfillment to describe why God and Christianity are important to them. …

Given the history of youth ministry and juvenilization, this pattern of religious beliefs should come as no surprise. As early as the 1950s, youth ministry was low on content and high on emotional fulfillment. The best youth ministries did provide individualized spiritual formation and even intense discipleship. But even otherwise exemplary youth ministries could unintentionally send the message that the church or even God exists to help me on my journey of self-development. … As they listen to years of simplified messages that emphasize an emotional relationship with Jesus over intellectual content, teenagers learn that a well-articulated belief system is unimportant and might even become an obstacle to authentic faith. This feel-good faith works because it appeals to teenage desires for fun and belonging. It casts a wide net by dumbing down Christianity to the lowest common denominator of adolescent cognitive development and religious motivation.

The content and the consequences of juvenilized Christianity are nicely summarized near the end of Bergler’s article.

Today many Americans of all ages not only accept a Christianized version of adolescent narcissism, they often celebrate it as authentic spirituality. God, faith, and the church all exist to help me with my problems. Religious institutions are bad; only my personal relationship with Jesus matters. If we believe that a mature faith involves more than good feelings, vague beliefs, and living however we want, we must conclude that juvenilization has revitalized American Christianity at the cost of leaving many individuals mired in spiritual immaturity.

What to do? Bergler offers several suggestions for “taming juvenilization.”

- Local congregations must learn to build an intergenerational way of life that fosters spiritual maturity.

- Pastors and youth leaders can begin by teaching what the Bible says about spiritual maturity, with a special emphasis on those elements that are neglected by juvenilized Christians.

- Church leaders also need to ask hard questions about the music they sing, the curriculum materials they use, and the ways they structure activities.

- We need to ditch the false belief that cultural forms are neutral. Every enculturation of Christianity highlights some elements of the faith and obscures others.

- We must be vigilant and creatively compensate for what gets lost in translation when we use the language of youth culture. For example, if we sing songs that highlight the emotional consolations of the faith, what can we do to help young people also embrace the sufferings that come with following Jesus?

I would suggest that Bergler’s article presents the church with a dual challenge—this is my analysis, not his. Grow up! Help your young people grow up!

Teenagers can legitimately follow Christ in adolescent ways, including participating in age-appropriate youth ministries. But those ministries must also help youth catch a vision for growing up spiritually. Churches full of people who are building each other up toward spiritual maturity are not only the best antidote to the juvenilization of American Christianity, but also a powerful countercultural witness in a juvenilized society.

Thomas E. Bergler is professor of ministry and missions at Huntington University, where he has taught youth ministry for 12 years. He is the author of The Juvenilization of American Christianity (Eerdmans, 2012), from which this Christianity Today article is adapted. He serves as senior associate editor for the Journal of Youth Ministry.

July 23, 2012

July 23, 2012

Google “Youth Specialties”. They go beyond Juvenilization in promoting Mysticism and Inter-spirituality